A new version of Mina Docs is coming soon! This page will be rewritten.

Snark Workers

Intro

While most protocols have just one primary group of node operators (often called miners, validators, or block producers), Mina has a second group — the snark worker.

Snark workers are integral to the Mina network's health because these nodes are responsible for snarking, or producing SNARK proofs, of transactions in the network. By producing these proofs, snark workers help maintain the succinctness of the Mina blockchain.

In this document, we'll briefly cover why snark workers are needed, how the economic incentives align, and provide operational details of performing snark work. Feel free to click through to any of the sections above that are most relevant to your needs.

Note: This document primarily targets node operators, and will not cover the theory of zk-SNARKs. Deep knowledge of SNARKs is not required to read this section, but it will be helpful to know roughly how SNARKs work and what they are useful for. If this is not the case, please check out this primer on SNARKs first.

Why Snark Workers?

Mina's unique property is the succinct blockchain. Each block producer, when they propose a new block to the network, must also include a zk-SNARK along with that block. This allows nodes to discard all historical data that's been finalized, and retain just the SNARK. If you are unfamiliar with the Mina protocol, this video is a good start.

However, it is not only sufficient for the block producers in Mina to generate SNARK proofs of blocks. Transactions also need to be snarked. The reason is because the blockchain SNARK does not make any statements of the validity of the transactions included in the block.

For example — let's say the current head of the blockchain has a state hash a6f8792226... , and we receive a new block with a state hash 0ffdcf284f... . This block will contain all the transactions that the block producer has chosen to include in this block, and associated metadata. We will also receive an accompanying SNARK that verifies the statement:

"There exists a block with a state hash 0ffdcf284f which extends the blockchain with a previous best tip with state hash a6f8792226."

Notice that this statement says nothing about the validity of the transactions included in the new block. If we were to believe this SNARK, and do nothing else, we may be tricked by a malicious block producer sending this block. Luckily, we have the raw block and we can check each transaction to ensure it is valid. But what about nodes in the network that may just want to receive the proof and not verify each block?

Snarking Transactions

In order to ensure that nodes can operate without trust on the Mina, it is important that each node can verify the state of the chain without needing to replay the transactions. In order for this to work, the above blockchain SNARK is not enough. We need to know that the transactions are also valid. Well, since SNARKs are good for exactly that, the naive suggestion might be to generate a SNARK of each transaction as they come in, and then combine them.

However, generating SNARK proofs is computationally expensive — if we had to compute SNARKs serially for each transaction, throughput would be very low and block times would skyrocket. Furthermore, transactions in a real world environment arrive asynchronously, so it would be very tough to predict when to perform the next item of work.

Lucky for us, we can leverage two properties about SNARKs:

- proofs can be merged - two proofs can be combined to form a merge proof

- merges are associative - merge proofs are identical, regardless of the order merged

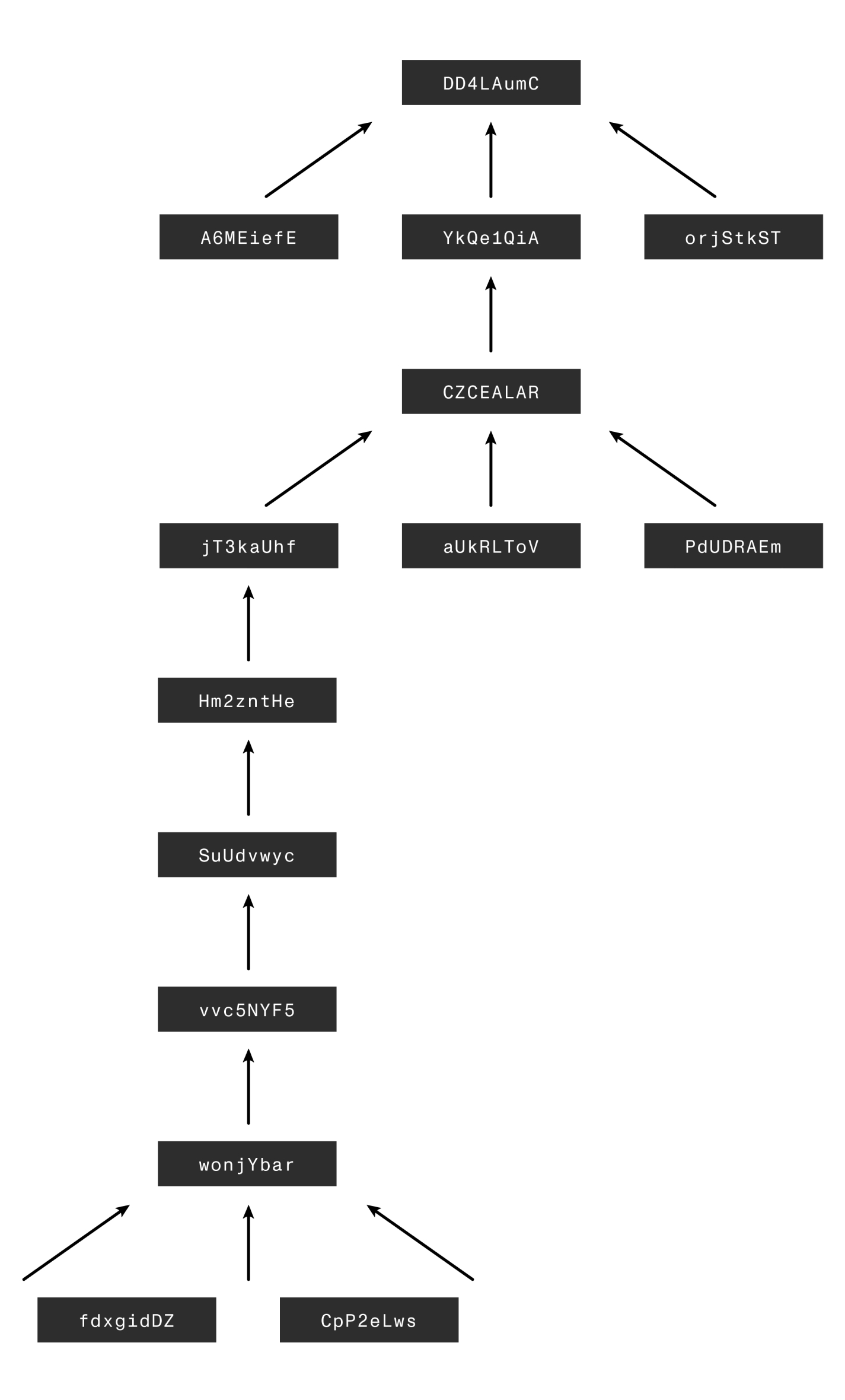

What these two properties essentially allow us to do is take advantage of parallelism. If proofs can be merged, and it doesn't matter how they're combined, then SNARK proofs can be generated in parallel. Whichever proof is finished first can be combined later with the proofs in progress. This can be envisioned as a binary tree, where the bottom row (the leaves) consists of the individual transaction proofs, and each parent row, the set of respective merge proofs. We can combine these all the way to the root, which represents a state update performed by applying all the transactions.

In addition, because the SNARK proofs don't depend on each other and we can exploit parallelism, this means anyone can do the work! The end result is that the distributed work pool is permission-less. Anyone with spare compute can join the network as snark workers, observe transactions that need to be snarked, and contribute their compute. And of course, they will be compensated for their work in what we affectionately call the snarketplace.

Note: To learn more about the details of how this snark work scheme evolved, it is highly recommended to watch this video: High Throughput with Slow Snarks. If you're interested in functional programming and the details of the scan state (the tree structure described above), we have a video covering the technical details.

The Snarketplace

The key dynamic to understand about snark work is:

Block producers use their block rewards to purchase snark work from snark workers.

There is no protocol involvement in pricing snarks, nor are there any protocol level rewards for snark workers to produce snarks. The incentives are purely peer-to-peer, and dynamically established in a public marketplace, aka the snarketplace.

You may ask, why does a block producer need to buy SNARKs? Fair question — the reason is because of what we mentioned earlier. In order to know for sure the state at the head of the Mina blockchain is valid, the transactions need to be snarked. But if we keep adding more transactions without snarking them at an equal rate, then over time we accumulate work that never gets finished. In order to reach a steady state equilibrium, we need work to be processed at roughly the same rate that work is added.

Since block producers profit from including transactions in a block (through transaction fees and the coinbase transaction), they are responsible for offsetting the transactions by purchasing an equal number of completed snark work, thereby creating demand for snark work. However, their imperative is to purchase snark work for the lowest price from the snarketplace. Conversely, the snark workers want to maximize their profit while also being able to sell their snark work. These two roles act as the two sides of the marketplace, and over time establish an equilibrium at a market price for snark work.

How to price snark work

We anticipate the snarketplace to dynamically rebalance — eg. follow the simple laws of supply and demand. While each snark work applies to a different transaction, seen from a larger perspective, snark work is largely a commodity (meaning it doesn't matter which snark worker produces the good — it will be the same). However, there are some nuances, so it may help to have some heuristics for pricing strategy:

- if market price is X, it is likely effective to sell snark work for any price below X (eg. X - 1), provided it is profitable after operating expenses.

- block producers are incentivized to purchase more units of snark work from the same snark worker because there will only be one fee transfer transaction they have to include in the block.

- Basically, the way a block producer pays a snark worker is through a special type of transaction called a fee transfer. The BP's incentive is to minimize the number of fee transfers, as each is a discrete transaction that needs to be added to a block (and consequently offset by more snark work). Thus, the best case scenario is to buy a bundle of snark work from the same snark worker.

- some snark work will be more important to complete ahead of other work, as it would free up an entire tree worth of memory (see the video above for more details). This is made possible by different work selection methods. Currently, the two methods supported natively are sequential and random. Neither of these however takes advantage of dynamic markets, which is an area of improvement that the Mina community can develop solutions for.

Since all the data around snarks and prices are public, there are several ways to inspect the snarketplace. One example is using the GraphQL API, and other options include using the CLI, or rolling a custom solution that tracks snarks in the snark mempool.

Stay tuned for more detailed analysis on snarketplace dynamics. We will also be releasing an economic whitepaper shortly that will provide more context.

See also: SNARKs and Snark Workers FAQ